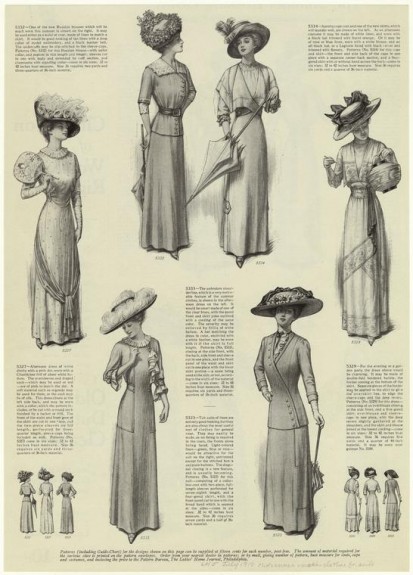

In the age before the Roaring Twenties, women were still wearing floor-length dresses. Waists were cinched. Arms and legs were covered. Corsets were standard on a daily basis. Hair was long. The Gibson girl was the idealized image of beauty. And the Victorian attitudes toward dress and etiquette created a strict moral climate.

Then the 1920s hit and things changed rapidly. The 19th Amendment passed in 1920 giving women the right to vote. Women began attending college. The Equal Rights Amendment was proposed by Alice Paul in 1923. World War I was over and men wanted their jobs back. Women, though, who had joined the workforce while the men were at war, had tasted the possibility of life beyond homemaking and weren’t ready to relinquish their jobs. Prohibition was underway with the passing of the 18th Amendment in 1919 and speakeasies were plentiful if you knew where to look. Motion pictures got sound, color and talking sequences. The Charleston’s popularity contributed to a nationwide dance craze. Every day, more women got behind the wheels of cars. And prosperity abounded.

All these factors—freedoms experienced from working outside the home, a push for equal rights, greater mobility, technological innovation and disposable income—exposed people to new places, ideas and ways of living. Particularly for women, personal fulfillment and independence became priorities—a more modern, carefree spirit where anything seemed possible.

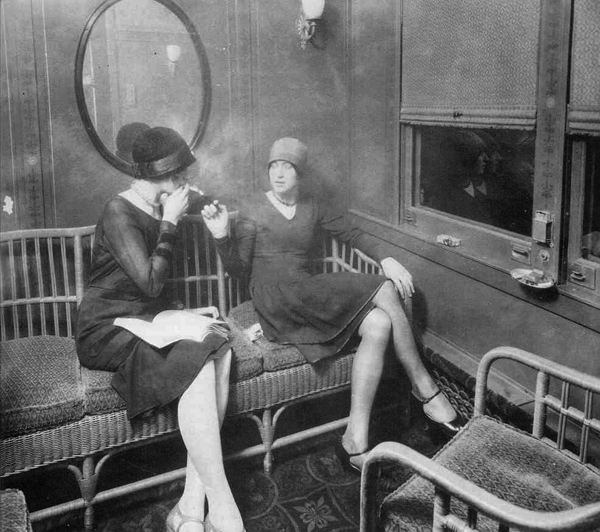

The embodiment of that 1920s free spirit was the flapper, who was viewed disdainfully by an older generation as wild, boisterous and disgraceful. While this older generation was clucking its tongue, the younger one was busy reinventing itself, and creating the flapper lifestyle we now know today.

It was an age when, in 1927, 10-year-old Mildred Unger danced the Charleston on the wing of an airplane in the air. What drove that carefree recklessness? For the most authentic descriptions that not only define the flapper aesthetic, but also describe the lifestyle, we turn to flappers themselves.

In A Flapper’s Appeal to Parents, which appeared in the December 6, 1922, issue of Outlook Magazine, the writer and self-defined flapper Elllen Welles Page makes a plea to the older generation by describing not only how her outward appearance defines her flapperdom, but also the challenges that come with committing to a flapper lifestyle.

If one judge by appearances, I suppose I am a flapper. I am within the age limit. I wear bobbed hair, the badge of flapperhood. (And, oh, what a comfort it is!), I powder my nose. I wear fringed skirts and bright-colored sweaters, and scarfs, and waists with Peter Pan collars, and low-heeled “finale hopper” shoes. I adore to dance. I spend a large amount of time in automobiles. I attend hops, and proms, and ball-games, and crew races, and other affairs at men’s colleges. But none the less some of the most thoroughbred superflappers might blush to claim sistership or even remote relationship with such as I. I don’t use rouge, or lipstick, or pluck my eyebrows. I don’t smoke (I’ve tried it, and don’t like it), or drink, or tell “peppy stories.” I don’t pet.

But then—there are many degrees of flapper. There is the semi-flapper; the flapper; the superflapper. Each of these three main general divisions has its degrees of variation. I might possibly be placed somewhere in the middle of the first class.

She concludes with:

I want to beg all you parents, and grandparents, and friends, and teachers, and preachers—you who constitute the “older generation”—to overlook our shortcomings, at least for the present, and to appreciate our virtues. I wonder if it ever occurred to any of you that it required brains to become and remain a successful flapper? Indeed it does! It requires an enormous amount of cleverness and energy to keep going at the proper pace. It requires self- knowledge and self-analysis. We must know our capabilities and limitations. We must be constantly on the alert. Attainment of flapperhood is a big and serious undertaking!

The July 1922 edition of Flapper Magazine, whose tagline was “Not for old fogies,” contained “A Flappers’ Dictionary.” According to an uncredited author, “A Flapper is one with a jitney body and a limousine mind.”

And from the 1922 “Eulogy on the Flapper,” one of the most well-known flappers, Zelda Fitzgerald, paints this picture:

The Flapper awoke from her lethargy of sub-deb-ism, bobbed her hair, put on her choicest pair of earrings and a great deal of audacity and rouge and went into the battle. She flirted because it was fun to flirt and wore a one-piece bathing suit because she had a good figure, she covered her face with powder and paint because she didn’t need it and she refused to be bored chiefly because she wasn’t boring. She was conscious that the things she did were the things she had always wanted to do. Mothers disapproved of their sons taking the Flapper to dances, to teas, to swim and most of all to heart. She had mostly masculine friends, but youth does not need friends—it needs only crowds.

While these descriptions provide a sense of the look and lifestyle of a flapper, they don’t address how we began using the term itself. The etymology of the word, while varied, can be traced back to the 17th century. A few contenders for early usages of the term include:

While the origin story differs depending on where you look, cumulatively, they all contribute to our perceptions of this independent woman of the 1920s. In the posts that follow, we’ll turn our attention to how those parameters set forth by Ellen, Zelda and Flapper Magazine are reflected in women’s attire we now associate with the 1920s, from undergarments to makeup and hair.

Flappers smoking cigarettes in a train car

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

Emily Spivack creates and edits the sites Worn Stories and Sentimental Value. She lives in Brooklyn, NY.